Entomology IV - Physiology

- SciSteins

- May 3, 2020

- 4 min read

So far, we have explored some neat and diversified external features. In this installment, you’ll be a leaf 🌱 following the path of food into the insect’s digestive tract. You’ll understand the flow of the hemolymph and why insects were so huge during the Carboniferous period.

PATH OF FOOD

The digestive tract has 3 parts, having each different functions. There's the foregut (also called stomodeum), the midgut (mesenteron) and the hindgut (proctodeum). To understand the insect's digestive system, let’s imagine you’re a leaf 🌱, about to get chewed by a giant grasshopper. Not a glorious end, but we'll use it for sake of understanding… First, the grinding mandibles of its hypognathous head will cut you off your plant substrate (you'll be detached from it by a powerful force, relative to your weight 🍃), then, the palps of the insect will push you into its mouth. The journey begins, it’s dark inside. You move from mouth to pharynx and from pharynx to esophagus (till here, the path is not different from a human). You exit the esophagus and enter the crop, which like a cellar, is used as a food storage, before digestion.

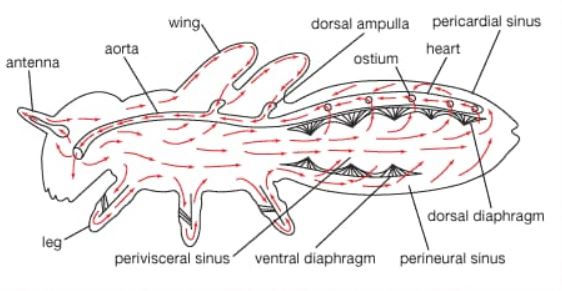

Your voyage continues into the proventriculus, which secretes hydrochloric acid (HCl) and pepsinogen and churns food - which sadly means YOU, with cuticular teeth that grinds it all through muscle movement. By the way, the foregut and the hindgut's roof are covered in a protective sheet called cuticular lining, which protects the insect from hard leaf material, in this case from you. So, in no way, is the insect going to get hurt by your cell wall. Once this is done, the insect filter's what is noxious to him – nitrogenous waste - this is what our kidneys do, but instead of kidneys, they have something called Malpighian tubules. Then, what's not useful is discarded - insect droppings. They're dry because the water produced to dampen the food has been reabsorbed in the hindgut. The droppings of larvae are called frass in the scientific community… Yes, they gave a scientific name to insect poop that only they will understand 🙄 A little side note: Butterflies and moths (Lepidopters) and flies (Dipters) as well as other insects that have piercing sucking mouthparts, do not have a proventriculus nor a cuticular lining (the protective cuticular sheet on the roof of their tract) because their diet consists solely of liquids - no need to protect against hard cellulosic or chitinous debris. CIRCULATORY SYSTEM Let’s move onto the 2nd system I want to talk about. Circulation! Let’s clarify something first, insects do not have blood. Repeat: They do NOT have blood. We can’t talk of blood because they don’t have hemoglobin, instead their body is filled with a liquid called hemolymph, a liquid mixture containing hemocytes, proteins, plasma and electrolytes. The hemolymph bathes and slouches around, enveloping the organs in a cavity called hemocoel. This is why, we talk about an open circulatory system.

The circulation is accomplished by a tubular heart (dorsal vessel) and a series of mini pumping organs. The alary muscles contract and expand the dorsal vessel to produce a hydrostatic pressure, which pushes the hemolymph forward. It accomplished what our heart does. The hemolymph is pumped forward by the dorsal vessel through the aorta into the head and flows back through the body in the hemocoel. It reenters the posterior heart through the ostia and the cycle repeats. There is yet another thing to clarify: The circulation does not carry oxygen in insects. O2 travels through a system of pipes called the tracheal system. The circulation only transports nutrients, hormones and waste products to the excretory systems. It protects against parasites thanks to the hemocytes and maintains the shape of the body through hydrostatic pressure.

WHY WERE INSECTS SO HUGE BACK THEN?

Here, you’ll finally understand why insects were huge during the Carboniferous period. But first, you must understand the basics of insect breathing.

Insects have spiracles which are holes on the lateral sides of their body. Air enters through them and travels in the tracheal system. The trachea divides into smaller pipes called tracheoles where gas is exchanged (O2 for CO2).

During periods of inactivity or diapause, the spiracles are kept closed and open only periodically. This is referred to as discontinuous gas exchange. Airflow can also be facilitated by pumping the thorax and abdomen. Some insects also coordinate the opening and closing of the spiracles to help create unidirectional airflow in the main trachea. Specifically, anterior spiracles are open during air intake and posterior ones are open when the air is expelled.

Bee pumping abdomen to facilitate air flow

Now to the crispy part, why were insects so huge back then❓

The reason is simple:

The rate of gas exchange (CO2 and O2) depends on 2 things. The first one is the diameter of the tracheae, which can be enlarged in some species in low oxygen environments to allow greater airflow. The second factor is the distance of diffusion, which is typically more important. The longer the distance, the longer O2 will have to travel through diffusion (there is no hemoglobin to carry it) to get to the cells.

During the Carboniferous period (350-300 million years ago), the skies were home to dragonflies with wingspans measuring almost 75cm (Meganeura) and other giant arthropods such as Arthropleura. Back in the day, the oxygen was more abundant in the air, so it would diffuse more easily through the long trachea and reach the cells. Remember that the rate of gas exchange is negatively correlated with the distance of diffusion, in other words if the length of the tracheal system is increased but the O2 is decreased, there is a lack of oxygen supply!

Nowadays, there is less oxygen in the air, so the insects had to adapt by reducing their tracheal length in order to maintain the same rate of gas exchange that they used to have during the Carboniferous period. So, evolution favored a small size. If you understood this last part, it means you understood insect breathing! 😤👍

Top: Arthropleura Bottom: Meganeura Both from the Carboniferous period, aka the Period of oxygen, trees and swamps!

SOURCES - My Uni lectures (won't mention the name of my uni for privacy reasons) - Lectures from another uni - University of Alberta: Bugs 101: Insect-Human Interaction. Can be found on Coursera

- 2 Books on entomology which names I don't remember. They're in my uni library, I'll add the titles when this whole covid mess is over and I can go back to uni.

- Lifeyard

_JPG.jpg)

Comments